The human laugh, that spontaneous burst of air and emotion, might seem like a simple reflex, but delve deeper, and you'll find a sophisticated interplay of history, culture, and language at its core. Unpacking the Historical & Cultural Roots of Verbal Humor reveals not just how we've tickled each other's funny bones, but how humor itself acts as a mirror, reflecting our societies, our anxieties, and our deepest linguistic quirks across millennia.

It's a journey into the very architecture of language, exploring how we twist words, play with meanings, and craft narratives that evoke that delightful, often insightful, release of laughter. From ancient Roman rhetoricians to modern neuroscientists, the question of why we find certain things funny, and how that varies globally, has fascinated thinkers for centuries.

At a Glance: Decoding Laughter

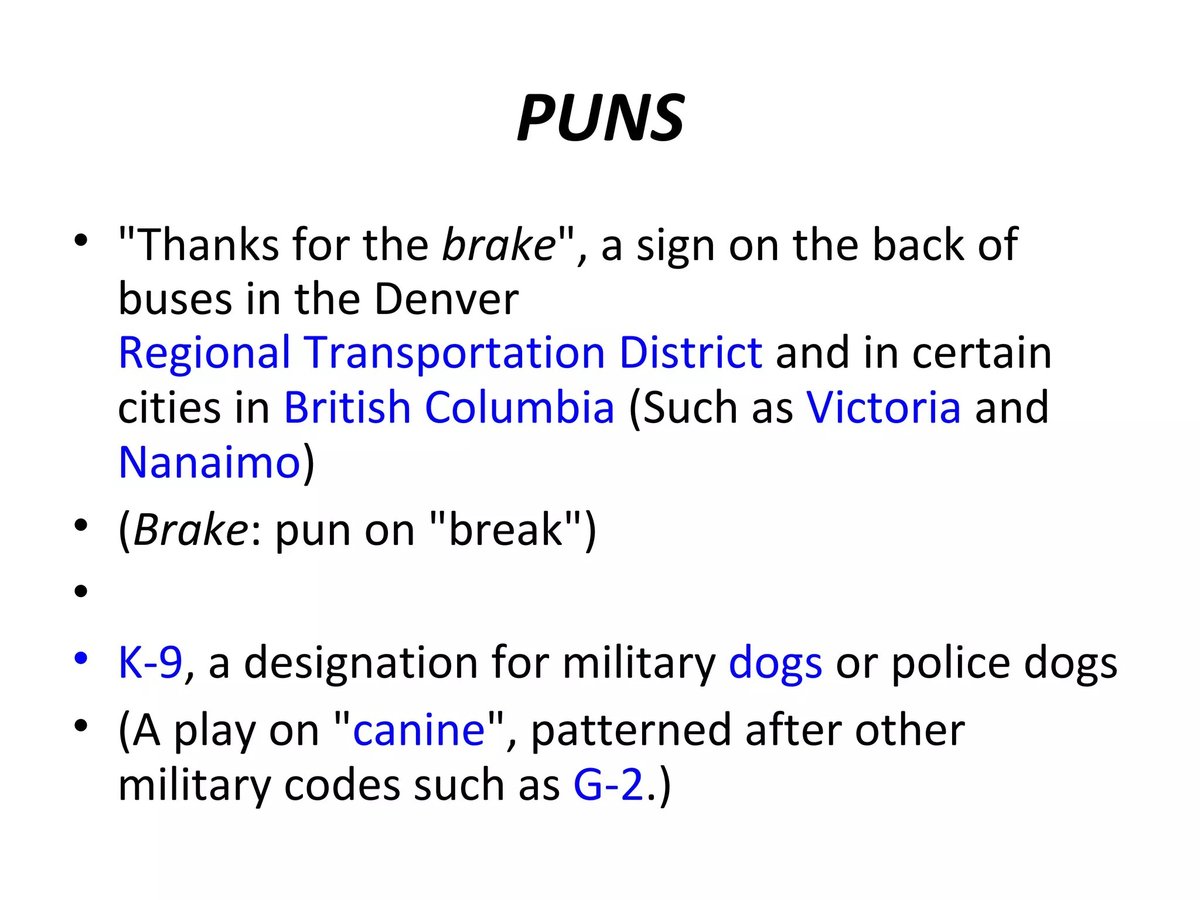

- Verbal vs. Referential Humor: Not all jokes are created equal. Some hinge on language itself (puns, wordplay), others on what they describe.

- Ancient Insights, Modern Science: Thinkers like Cicero were making distinctions about humor that neuroscientists are only now confirming with brain scans.

- Culture Shapes Comedy: What's hilarious in one country might be confusing or even offensive in another. Context is king.

- Beyond the Punchline: Humor is a powerful tool for social critique, bonding, and navigating complex situations.

- Learning to Laugh Together: Understanding these roots helps us appreciate diverse humor styles and communicate more effectively across cultural divides.

The Two Faces of Funny: Verbal vs. Referential Humor

Imagine a joke. What makes it funny? Is it the outrageous situation it describes, or the clever way the words are put together? This isn't just a philosophical musing; it's a fundamental distinction that scholars have pondered for centuries and that shapes the very essence of verbal humor.

For our purposes, we're talking about humor that crucially leans on the linguistic form—the actual sounds, structures, and words themselves—of an utterance. This is what we call verbal humor. It’s the kind of humor that suffers terribly, or dies entirely, when you try to translate or paraphrase it.

Contrast this with referential humor, which operates purely on the level of meaning and context. Referential jokes are funny because of what they describe, regardless of the specific words used, as long as the core meaning is preserved.

Cicero's Ancient Test: De Re vs. De Dicto

The Roman orator and philosopher Cicero was one of the earliest to articulate this divide, back in the 1st century BCE. He spoke of humor de re (humor of the subject matter) and humor de dicto (humor of the expression). His proposed test was elegantly simple: try to translate or paraphrase the joke. If the humor evaporates, it’s de dicto (verbal humor); if it survives, it's de re (referential humor).

Take the classic pun: "Why did the scarecrow win an award? Because he was outstanding in his field!" The humor here relies on the double meaning of "outstanding in his field" – excelling, and literally standing out in a field. Try to translate that directly into another language, and you'll likely lose the linguistic play. That's verbal humor.

Now, imagine a joke about a clumsy person tripping over their own feet. The humor comes from the visual image and the situation, not the specific words used to describe it. You could tell that story in many ways, or even mime it, and it would still be funny. That's referential humor.

The Modern Take: More Nuance, More Brain Science

Cicero's test, while insightful, isn't foolproof. A skilled translator might find an equivalent pun in another language, or some linguistic parallelisms can unexpectedly preserve humor across borders. Therefore, linguists today approach the distinction with a bit more precision. The real determinant is whether a full linguistic analysis requires reference to the formal levels of language (phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax) for the humor to be understood. If only semantics and pragmatics (word meaning and context) are sufficient, it's referential.

For instance, the pun "away for" versus "a wafer" demands attention to the phonetic or phonological similarities. Without that, it’s just nonsense. This is a clear case of verbal humor.

Interestingly, modern neurolinguistic research provides a fascinating corroboration of Cicero's ancient insight. MRI studies indicate that when people process verbal or phonological jokes, the Broca’s area of the brain—a region heavily involved in language processing—shows significant activation. Referential jokes, however, do not activate this area in the same way. This suggests a distinct neural pathway for appreciating humor rooted in linguistic form. Scholars like Violette Morin, Umberto Eco, Pierre Guiraud, Charles Hockett, and Sigmund Freud, though using different terminology, have all explored similar distinctions, further solidifying the idea that humor isn't a monolithic entity.

A World of Laughter: Cultural Tapestries of Humor

While the capacity for humor is a universal human trait, what makes us laugh, how we express it, and how we perceive it are profoundly shaped by our cultural backgrounds. Humor is less a universal language and more a collection of rich dialects, each with its own grammar of wit.

Verbal Dexterity vs. Physical Comedy

In many Western cultures, particularly English-speaking ones, there's a strong historical and cultural affinity for verbal humor. Puns, wordplay, sarcasm, irony, and dry wit are highly valued. These forms demand a sophisticated understanding of language, its nuances, and its potential for double meanings. British humor, with its often understated and ironic wordplay, is a prime example. American stand-up comedy, too, frequently relies on clever turns of phrase, observational wit, and linguistic dexterity.

Conversely, many Asian cultures often place a greater emphasis on physical humor and slapstick. Exaggerated actions, expressive gestures, and impeccable timing often take precedence over intricate verbal constructions. Think of classic silent films, which transcended language barriers with their physical comedy, or various forms of traditional and contemporary Asian entertainment where visual gags and physical antics are central to the comedic appeal. This isn't to say one type is superior, but rather that cultural preferences guide comedic expression.

Satire, Social Commentary, and the Limits of Laughter

Humor, especially verbal humor, has always been a potent tool for social and political critique. In Western countries, satire, parody, and caricature are commonly employed to challenge authority, criticize societal norms, or highlight injustices. Think of political cartoons, late-night comedy shows, or satirical novels, which often use sharp wit and linguistic manipulation to make their points.

However, in some other cultures, the use of humor to challenge authority or address sensitive topics might be viewed as less appropriate. Norms of respect for elders, leaders, or social hierarchies can dictate a more deferential approach, even in jest. Humor in these contexts might serve to reinforce social bonds or teach moral lessons rather than to subvert. Understanding these unwritten rules is crucial to navigating cross-cultural interactions without causing unintended offense.

Group Harmony vs. Individual Spotlight: Collectivism vs. Individualism

Cultural leanings towards collectivism or individualism also shape humorous expression. In collectivist societies, where group harmony and cohesion are paramount, humor often focuses on shared experiences, inside jokes that reinforce group identity, or lighthearted banter that avoids singling anyone out negatively. Jokes that might embarrass an individual or challenge group consensus are generally avoided to maintain social equilibrium.

Individualistic cultures, on the other hand, frequently embrace humor that highlights personal achievement, celebrates individuality, or even uses self-deprecation as a form of relatable honesty. Stand-up comedy, where a single performer commands the stage, is a quintessential individualistic comedic form, often featuring personal anecdotes and unique perspectives. The humor here can afford to be sharper, more confrontational, and more focused on individual expression. If you're looking for a way to express that sharp wit, sometimes a bit of playful provocation can do the trick; you might even Try our insult generator for some inspiration, understanding that the cultural context determines its reception.

The Indispensable Role of Context and Shared Knowledge

Humor is rarely a standalone entity; it thrives on context. A joke's effectiveness often relies on a deep understanding of specific language nuances, shared cultural references, or historical knowledge. British irony, for example, often requires listeners to grasp subtle inflections, unspoken assumptions, and a historical context of understatement. Similarly, American pop culture references or political in-jokes might be completely lost on someone unfamiliar with the specific cultural landscape.

This contextual dependency makes cross-cultural humor particularly challenging. What's hilarious to a native speaker steeped in the culture might simply sound confusing or bland to an outsider. It highlights that humor isn't just about language; it's about shared experience.

Professional Settings: When to Be Witty, When to Be Formal

The role of humor also varies significantly within professional settings across cultures. In some corporate cultures, particularly in individualistic Western contexts, lighthearted humor is encouraged to build rapport, foster team cohesion, and ease tensions. A well-placed witty remark can be seen as a sign of intelligence and social grace.

Conversely, in other professional environments, particularly in more hierarchical or formal cultures, maintaining strict professionalism with minimal humor might be preferred. Jokes, especially verbal ones that might be misinterpreted, could be seen as unprofessional, disrespectful, or distracting. Awareness of these differences is critical for successful cross-cultural collaboration and effective communication.

Non-Verbal Humor: The Universal Language with Local Dialects

While our focus is on verbal humor, it's worth noting that non-verbal humor (facial expressions, gestures, situational comedy) is often considered more universally understood. A silly face or a pratfall tends to elicit laughter across cultures more readily than a complex pun.

However, even non-verbal cues carry cultural nuances. Exaggerated gestures or loud, boisterous laughter might be perfectly acceptable and even encouraged in some cultures as a sign of genuine enjoyment, while in others, they might be considered impolite or overly boisterous. Understanding these subtle non-verbal cues is essential for improving overall social interaction and avoiding misinterpretations.

Weaving Wit Through Time: A Brief History of Verbal Humor's Roots

Tracing the historical roots of verbal humor means recognizing that language play and witty expression have been integral to human communication since antiquity. While the forms and social functions might evolve, the underlying mechanisms of linguistic manipulation remain constant.

Ancient Echoes: From Oratory to Philosophy

As we've seen with Cicero, the Romans were keenly aware of the power of language in humor, particularly in rhetoric and public speaking. A well-timed pun or a sharp epigram could sway an audience or deflate an opponent. Greek philosophers also debated the nature of comedy, recognizing its cognitive and social dimensions. This period laid the groundwork for understanding humor as more than just entertainment – it was a tool, a weapon, and a philosophical puzzle.

Medieval Merriment and Renaissance Rhetoric

The Middle Ages saw the rise of jesters and fools, figures whose role was often to use wordplay, satire, and clever inversions of logic to entertain nobility and, crucially, to speak uncomfortable truths shielded by the cloak of comedy. Their verbal dexterity allowed them to navigate strict social hierarchies.

The Renaissance brought a renewed interest in classical rhetoric and literature, further cultivating an appreciation for elaborate wordplay, paradoxes, and sophisticated wit in plays, poetry, and social discourse. Shakespeare, for instance, is a master of verbal humor, filling his plays with puns, double entendres, and clever repartee that are still dissected by scholars today.

Enlightenment Wit and Modern Mirth

The Enlightenment era in Europe fostered an environment where wit, reason, and social critique often intertwined. Salons buzzed with clever conversation, and satirical essays became a potent form of political and social commentary, relying heavily on linguistic precision and intellectual dexterity.

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed the formalization of humor studies, with figures like Sigmund Freud attempting to unlock the psychological underpinnings of jokes, specifically highlighting how verbal jokes can serve to release repressed thoughts or reveal unconscious desires through linguistic disguise. The advent of mass media—radio, television, and now the internet—has amplified the reach of verbal humor, from stand-up comedy specials to viral memes that often rely on a quick, clever turn of phrase.

Beyond the Laugh: Practical Insights from Humor's Roots

Understanding the historical and cultural underpinnings of verbal humor isn't just an academic exercise; it offers practical benefits in our interconnected world.

Navigating Cross-Cultural Communication

- Listen Actively: Pay attention to the types of humor used in a new cultural context. Is it primarily verbal, physical, self-deprecating, or group-focused?

- Avoid Literal Translation: If you're unsure, don't try to translate a verbal joke directly. It's almost guaranteed to fall flat or be misunderstood.

- Contextualize Your Humor: Be mindful of sensitive topics. What's fair game for a joke in one culture might be deeply offensive in another.

- Err on the Side of Caution: When in doubt, it's often safer to stick to generally light, non-verbal humor or to observe before participating.

Crafting More Effective Communication

- Target Your Audience: Tailor your humor to the cultural background and linguistic understanding of your listeners.

- Master Specific Forms: If your goal is to be witty in a Western context, practice puns, irony, and clever wordplay. If it's more about physical comedy, focus on timing and expression.

- Use Humor Strategically: Verbal humor can build rapport, disarm tension, or make complex ideas more memorable. But misuse can alienate. Understand the distinction between verbal and referential humor to ensure your message lands as intended.

Appreciating the Art of Comedy

- Unpack the Layers: When you encounter a joke, consider: Is it verbal or referential? What linguistic elements make it funny? What cultural assumptions does it rely on?

- Broaden Your Palate: Explore humor from different cultures and historical periods. You'll gain a richer appreciation for human creativity and the diverse ways we find joy.

- Recognize Humor as a Cultural Barometer: Humor often highlights societal values, anxieties, and points of tension. By studying it, you learn more about a culture itself.

Common Misconceptions About Humor Debunked

You might hear a few prevailing ideas about humor that, while seemingly true, often miss the mark when viewed through the lens of its historical and cultural roots. Let's clear up some of the most common ones.

Misconception 1: "A good joke is a good joke anywhere."

- Reality: While the capacity for humor is universal, the specific content and form of humor are intensely culturally specific. What's funny relies heavily on shared language, cultural context, and societal norms. A brilliant pun in English is utterly meaningless in Chinese unless an equivalent linguistic play exists.

Misconception 2: "Humor is just about making people laugh." - Reality: Laughter is the primary outcome, but humor serves many deeper functions. Historically and culturally, it's been used for social bonding, teaching moral lessons, challenging authority (as satire), coping with stress, expressing complex ideas, and even as a form of social control or exclusion.

Misconception 3: "Non-verbal humor is truly universal." - Reality: While more universally understood than verbal humor, non-verbal cues (like exaggerated expressions or gestures) still carry cultural nuances. The intensity, appropriateness, and meaning of a "funny face" or a loud laugh can differ significantly from one culture to another. What's boisterous joy in one place might be seen as rude in another.

Misconception 4: "Humor always needs to be kind or gentle." - Reality: Many cultures, particularly individualistic Western ones, have a robust tradition of sharp, biting, or even aggressive verbal humor like sarcasm, insults (often playful), or dark wit. The appropriateness of such humor is highly context-dependent, often requiring strong social bonds and mutual understanding to be received as humor rather than hostility.

The Enduring Power of Wordplay

From ancient Roman forums where Cicero wielded wit as a rhetorical weapon, to the modern stand-up stage where comedians craft intricate verbal tapestries, the Historical & Cultural Roots of Verbal Humor reveal a profound truth: our laughter is intricately woven into the fabric of our language and our shared human experience.

Understanding this journey isn't just about appreciating a well-timed punchline; it's about recognizing the sophisticated dance between sound and meaning, the delicate balance between cultural norms and comedic subversion, and the enduring human need to connect, challenge, and cope through the power of words. So next time you hear a joke, pause for a moment. Is it the situation that's funny, or the clever twisting of words that makes you chuckle? You might just find yourself appreciating the artistry of humor on a whole new level.